How to Use Deliberate Practice to Learn a New Language

If you knew it would take 10 years to get fluent, would you still commit to it?

This article was originally published on my Medium site, and contains a few updates.

Figuring out the “why” of your language fluency goal is the easy part — you want to live in a new country, or create a new business, or meet the love of your life. But in my experience, it’s inevitable to second-guess my future success when things get tough, or even worse, when I’m close to a breakthrough.

One of the pieces of advice you’ll hear every year between December 1 — January 13 (New Year’s resolutions time) is that you should focus on the process to a goal, rather than the goal itself.

A cheat code for life is that if someone else has already figured out the easiest way to do something, then just do that. The funny thing is, to be great at a skill, the easiest way is quite difficult.

Deliberate Practice is a term coined by K. Anders Ericsson and colleagues about the results of the research they did to determine why the best are better than everyone else. Basically, they don’t go through the motions. Instead, they practice conscientiously with a focus on improvement and have teachers and coaches to give them feedback.

I think it sounds perfectly reasonable to apply this same logic to learning a new language. After all, you went through years of tests and essays to learn how to speak like an intelligent adult in your native tongue, right?

What they write in the HBR article:

“The journey to truly superior performance is neither for the faint of heart nor for the impatient. The development of genuine expertise requires struggle, sacrifice, and honest, often painful self-assessment. There are no shortcuts. It will take you at least a decade to achieve expertise, and you will need to invest that time wisely, by engaging in ‘deliberate’ practice — practice that focuses on tasks beyond your current level of competence and comfort.”

Frustration is inescapable if you intend to grow. Some of us weren’t lucky enough to develop the ability to compartmentalize our thinking in foreign languages early in our lives, so growing pains are especially hard. I can’t be the only one who expected to be speaking a new language fluently in less than a year after starting to study in earnest. The key is to not descend into negative self-talk when you meet these barriers, which will cause you to stop your learning process.

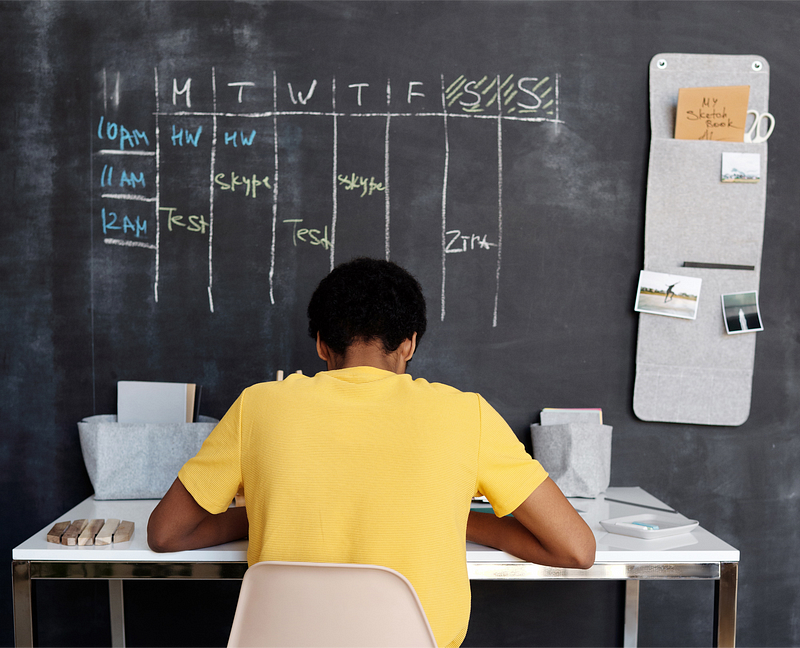

A good first step is to identify two areas of focus. First, what you are doing well — a thing you can improve easily to keep your motivation up. Second, what your biggest pain point is that will need a lot of time and effort to improve.

Having a pro give you feedback is great, but there are other ways to track your progress when you don’t have access. If you are advanced, take an average of the number of words you have to look up per page every once in a while. How did that number change over time?

If you are intermediate, keep a weekly journal, where you congratulate yourself on using a difficult verb mood or finally remembering how to use a difficult conjunction properly.

For my beginner friends, count how many words you recognize on a menu, what you can name in your kitchen, in which ways you can cuss out an ex, etc.

It depends on what your goals for the present time are — increasing your vocabulary, getting the hang of verb usage, understanding tough accents, and so on.

So what to do when times get tough? Do something else. The great thing about learning a new language is that we have a lot of options to practice.

If you feel like you’re stagnating after doing a lot of listening to podcasts, then try reading comic books to improve your conversational vocabulary. After that, you can memorize a block of text and recite it like an actor. If you’re brave, record yourself speaking out loud and take notes on your pronunciation. Or perhaps translate poetry from your native language to your target language, following the same poem structure. Then, look at a documentary about the history of the language you are learning.

You get the picture.

And take some time to return to your why to refute your self-sabotaging doubts. Use tools that keep you inspired: create a vision board if you are visual, or write about how your first trip to Mongolia will be the best experience ever if you’re a wordsmith.

I’ll repeat a key sentence from the HBR article for those who missed it: there are no shortcuts.